On Friday afternoon I led a Bible study with a circle of men in the Fresno County Jail. It included entering the biblical story ourselves and experiencing Jesus countering voices of shame we hear. I passionately invited them to imagine Jesus’ loving gaze when they hear shaming voices. One way or another, I address shame about once a month in the jail Bible study. Why so often?

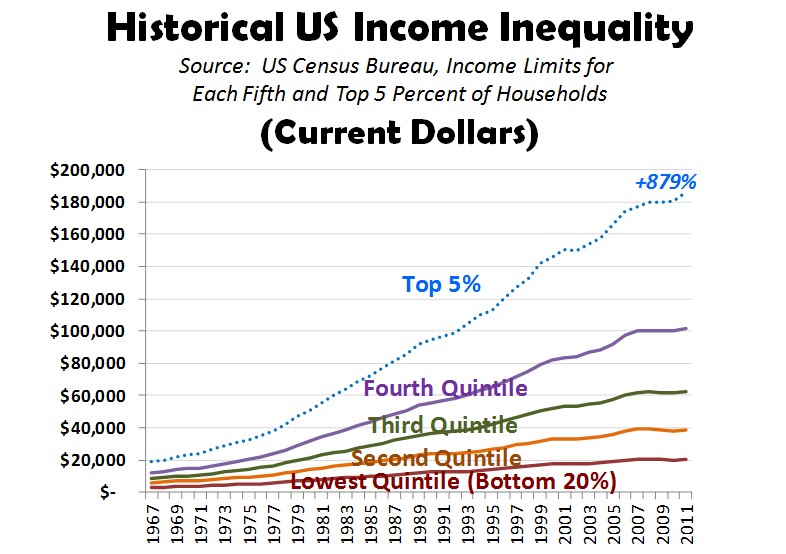

Inequality feeds violence. James Gilligan, a psychiatrist who served as director of mental health for the Massachusetts prison system, explains that dividing people into categories of superior and inferior feeds violence. He states that as societal inequality increases so does violence. In a previous blog and in a section of this website, I have summarized research that shows that many problems, not just violence, increase with inequality—and everyone is affected, not just the poor. Why? Why does greater inequality feed these problems? Gilligan’s writing on violence powerfully displays the answer. At the root of violence, he found shame; and increased inequality is a catalyst for shame. My friend, and sociologist, Bob Brenneman found the same thing in his research on why people join gangs in Central America. There are a number of contributing factors, but the one that stood out was shame. Therefore, as we work for shalom, two key things to pursue are lessening inequality and healing shame.

The men in the Bible study come from a high security pod. Most are gang members. Violence is a part of their past, if not their present. What would Gilligan’s and Brenneman’s books tell me? If I dig beneath the tattoos and the criminal records what will I find? Shame. Therefore, I frequently proclaim liberation from shame through Jesus. That Friday, after doing the shame-healing exercise we had a time of prayer. I invited them to speak the names of people they love who have needs that the inmates themselves cannot address or solve. By naming them we would be asking God to bless them and do what we are unable to do.

We spoke names, one at time. The names kept coming, often tumbling one over the other—rarely a gap of more than a few seconds. I felt loving concern echo off the cement block walls. After five minutes I spoke a brief closing prayer—not because of awkward silence, but because our time was up. We shook hands, embraced. They thanked me for coming. Robert said, “thank you I needed this today. I look forward to Friday’s. This is reorienting.”

After the correctional officer took the men back to their pod he came to unlock the closet where I turn in my report on how many attended. He asked me, “How were they?” From time to time a C.O. asks me a “how did it go?” question that feels supportive, interested. This felt different. I replied, “Fine, it was a good study. They engaged well. They treat me well. Thanked me for coming.” All he said in reply was, “they are the worst of the worst.” I assume he was making a general comment about them coming from one of two high-security pods in the building. I guess on paper, if you look at the number of past infractions, and assume that tells you who they are—then yes, “worst of the worst.” But the words shocked me. I did an internal double-take. “What did he just say?” Is he talking about the same men who just lovingly prayed for others? Who thanked me for coming? Yes, they acknowledge they have done bad things in the past, but they long for a chance to live differently and not be defined by their past. As I rode home on my bike I pondered those words, “worst of the worst.” How does that categorization seep out through the words, the looks, the actions of that C. O. and shower the men with shame? What does it do to the men to wear that label? If Gilligan is correct, that correctional officer and the shaming system he is a part of will increase, not decrease the level of violence in society. I do Bible studies to counter shaming voices frequently . . . perhaps not frequently enough.

Thankfully, however, not everyone in the system thinks and acts as that officer does. Earlier this year I was walking with a different correctional officer to same closet. I said, “How have you been? I have not seen you for a while.” He replied, “I was on yard duty.” I asked, “Is that good or is it better to be on one of the floors?” He said, “You could say it was punishment.” I did not press for more information, but he went on. “I refused to do something I was told to do, because it was not right. These men are people too.” He named the number of a legal code, and said, “I refuse to go against that code.” I then asked him if he had heard of Bryan Stevenson and told him about the line from his book Just Mercy, “Each of us is more than the worst thing we've ever done.” He said, “yes, I have done bad things. These men have done bad things too, and yes, the quote is right.” Then he said, “I call them men, I do not call them inmates.”

He has worked in the jail and before that prisons, for years. This week I heard him say to another. C.O. that he had not had a break all day. I asked him why. He said, “A couple of the other guys working are new. I can’t leave them alone. The men would eat them alive.” (I assume he meant take advantage of them.) He is not naïve, but unlike the other C. O. he works with intentionality to lessen shame. He refuses to divide them into an inferior category.

Which of these two men represents more accurately the system as a whole, society as a whole? Sarah Koenig, of the Serial podcast, has spent months interacting with people in Cleveland’s criminal justice system. How would she answer the question? I listened to the first episode of season three while working in our garden. Her words near the end of the episode led me to put down my spade and, through the lens Gilligan’s work, sadly ponder the implications of what she said.

A felony judge I was talking to for a different story in this series told me he was thinking of giving a defendant serious time. “What's serious time?” I asked. He explained, well, to someone with common sense, even one day in jail is devastating, life changing. To someone who's got no common sense, maybe they do three years, five years. Means nothing. They go right back out and commit more crimes.

I knew what he meant. Punishment is relative. What it takes to teach you a lesson depends on what you're used to. But there was a more disturbing implication as well. One that prowls this courthouse and throughout our criminal justice system. That we are not like them. The ones we arrest and punish, the ones with the stink, they're slightly different species, with senses dulled and toughened. They don't feel pain or sorrow or joy or freedom or the loss of freedom the same way you or I would.

“We are not like them.” What a potent shaming mechanism prowling through our justice system and society.

To be an agent of peace is not just to defuse and de-escalate a situation of active violence. It is also to work at the root causes of violence. James Gilligan would tell us that includes lessening the inequality gap, alleviating shame and building dignity. Clearly Jesus knew this before Gilligan. Whereas the first Correctional Officer’s words sound like things we hear from the Pharisees, Jesus’ words and actions match and go beyond those of the second officer.

What are ways we as individuals contribute to making distinctions between superior and inferior? What are ways our church communities do that? How do we participate in and go along with ways society builds the inequality gap?

What actions can we take toward dismantling or transforming systems that contribute to the inequality gap? How can we follow Jesus in alleviating shame and restoring dignity? What are ways we can lead the shamed to experience Jesus’s loving embrace?