His comment immediately seized my attention. It felt significant. It was. Forty years later I still remember the comment; I found it so important I tried to work it into as many courses as I could. Actually, before it grabbed my attention I had to first ask a question about a word our former professor had used. I asked John Linton what he meant by “ontological.” He had told us that it was more biblical to think of sin as a relational problem rather than ontological, he explained that “ontological” referred to our being. He invited Lynn and I to imagine that what we inherited from Adam and Eve was not something like a sin gene that corrupted our being, but rather a web of broken relationships we were born into.

I have recently been in conversations on this topic because my wife Lynn is reading John E. Toews’ book, The Story of Original Sin, and because my daughter Julia shared her negative reaction to someone describing our state of sin as ontological. In both cases my passion for the topic immediately switched on. I, mentally, reached into the file of my class notes and shared observations with them. In the midst of those conversations I had a new insight about how our view of sin can facilitate or hinder a centered-set approach. In this blog I will first give a short summary of how I described the two concepts of sin in class. Then I will share my new insight.

Two comments before I begin. First, to critique the biological-like view of sin and advocate for the relational view is not to downplay the severity or universality of sin. The question is what is the root cause of sin. Second, to those who might think, “Oh, just like a theologian to come up with some new idea rather than sticking with the old traditional view.” Well, in this case, the relational view is actually the older one! For more on that, see the first “footnote” at the end of the blog.

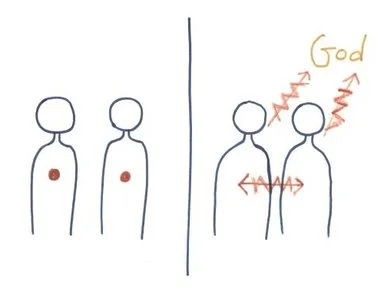

Sin as a relational problem — this view focuses on broken relationships as the root problem that causes us to sin. As illustrated on the right side of the above diagram, a lack of trust distorts our relationship with God, ourselves, others, and creation. Those twisted relationships lead us to commit actions that hurt God, damage ourselves, others, and creation. Humans are born into a web of distorted relationships that lead them to react in fear and mistrust. They are alienated and therefore they sin.

Sin as an ontological problem — this view focuses on a state of being as the root problem. In an almost biological sense it sees humans as tainted or corrupt. Humans are at the core of their being bad or evil and therefore do evil. Humans are ontological sinners and therefore they sin. Or, as illustrated in the left side of the above diagram, people think of sin like an ugly cancer within our being that causes us to commit actions that hurt God, damage ourselves, others, and creation.

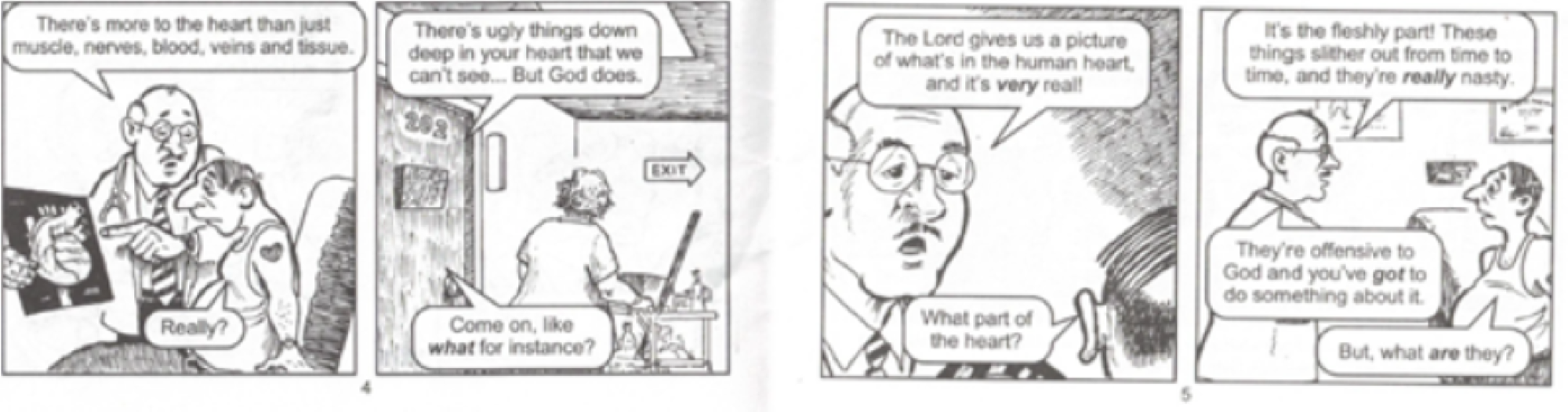

I have qualified my language with the word “like”—"like an ugly cancer,” “biological-like” and “like a sin gene.” The reality, however, is that many Christians do think of sin as passed on from generation to generation in a very physical way—as seen in this tract’s portrayal of sin. On the previous page, the doctor had said “Everybody’s born with a bad heart problem.”

Sins sliver out of the fleshly part of the heart

Later in the tract, the doctor says, “When Adam and Eve disobeyed God, everything changed, especially our hearts, and that got passed down to us.” Note, a relational view of sin would affirm almost everything in that sentence, but would say “relationships” instead of heart. It could use “passed down” language, but might more clearly say something like, “and we have all been born into that web of alienated relationships.” (The tract is, Heart Trouble?, Chick Publications, www.chick.com)

Although thinking of sin as part of our being in a physical sense is very common today, and seen by many as the orthodox view, it is not explicitly in the Bible, it was not used for the first 300 years of church history, and it was never adopted by the Eastern Orthodox churches.

Many of us have tended to read biblical passages on sin from an ontological perspective and think that they clearly state that our being is in some way evil or sinful, and therefore we sin. I maintain that those passages can be understood in line with the above paragraph on the relational paradigm of sin. So, for instance, when Paul talked about his old self, he could be referring to a human who is fundamentally alienated from God, others, and self. We can still talk of being born in sin, or born as sinners, but I would choose to interpret that in a relational sense (see the "web" language above).

Do we receive some gene or cancer that makes us sin, or do we receive from our parents and ancestors relational alienation? I maintain that at the root of sin is lack of trust or unbelief which is manifested in distorted relationships and which causes the actions we call sins.

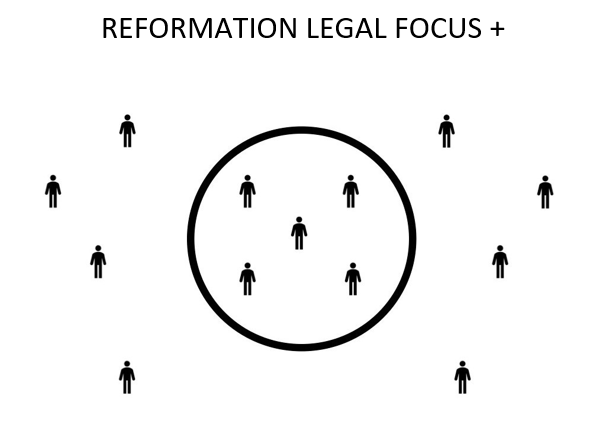

Bounded, Centered, and Our Concept of Sin

In class, after presenting the two concepts of sin I would ask, “what difference does this make in life? How will each concept lead people to think of themselves? How will your view of sin influence how you approach pastoral care, counseling, discipleship?” The ontological concept leads many people to think of themselves as unrepairable. From this perspective, a life of faith in Christ offers forgiveness for sinful acts caused by the sin gene and gives the hope of a body without the sin gene in heaven. In the meantime, the sin gene is present. If an individual, or church community, accepts that as reality, pastoral care and discipleship will likely be seen as sin-control—seeking to lessen the damage from a physically sinful heart.

In contrast, if the fundamental problem is viewed as broken relationships, then salvation through Jesus is not limited just to forgiveness and a future hope. Healing of alienation starts in the moment of salvation and can continue in this life on earth. Rather than just trying to build a containment wall around the root problem, the relational view understands that we can lessen the severity of the root problem. Pastoral care and discipleship will not bring full healing this side of heaven, but can significantly lessen alienation. In contrast to the ontological view, a relational approach will focus not only on the sin actions flowing from the root, but on the root as well.

I heard myself say something like that in the conversation with my daughter, and at that moment I noticed the similarity to the image and language of a bounded-set church. In many ways the bounded approach is about containment—sin control. The boundary wall is the key tool for behavioral change. In a centered-set church the key is relationship—relationship with the center and relationship with those who walk with us in becoming more Christlike. Therefore, an ontological view of sin will contribute toward a bounded church mentality and a relational view of sin will facilitate a centered approach. I want to be careful to not overstate. A church that teaches an ontological view of sin can still work at being centered—and benefit from doing so. Teaching a relational view of sin does not alone protect a church from being bounded or fuzzy. Rather, they both feel like compost. Adding an ontological view of sin to the soil of a church will enhance the sprouting and flourishing of a bounded-set church. Adding a relational view of sin to the soil of a church will enhance the sprouting and flourishing of a centered-set church.

Therefore, recognizing that many people who have never heard the term “ontological sin” nor read a theology book have an ontological view of sin, let us in our preaching, counseling, spiritual direction, and teaching explicitly challenge the sin-gene concept and replace it with the relational understanding of sin.

Footnote #1

The ontological understanding of sin traces back to Augustine, and sadly, to a poor translation of one verse. John E. Toews wrote that Augustine “consistently taught that sin originated in the transgression of Adam and was transmitted from generation to generation through human reproduction” (85). Augustine rooted his understanding of all humans inheriting sin from Adam in a seminal manner in Romans 5:12—a text he cites more than 150 times. Unfortunately, Augustine did not know Greek well and he relied on a Latin version that mistranslated the verse.

Instead of an accurate translation like:

“Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned—”

The version Augustine read said,

“Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, in whom all sinned—"

That “in whom all sinned” supported his idea that a piece of the soul was contaminated and passed through male semen.

Toews’s short book, The Story of Original Sin, provides not only a chapter detailing Augustine’s missteps, but more importantly displays how up until that time, both Jews and Christians, did not hold an ontological view of sin.

Footnote #2

When I presented this material in class, some students would argue for a combination of the two views. I always argued against that—seeing it as an effort to hang on to something I thought better to let go of. But about five years ago a student, Susan Tovar, argued for a combined view that led me to acknowledge that reality is more complex than my two neat categories. There can be a physically inherited aspect to sin. She said that recent studies in epigenetics point to traumas of ancestors, their fears and anxieties, being passed on genetically. These researchers would respond to what I have written by saying we not only are born into webs of broken relationships, but we are born with inherited trauma. We might say some woundedness is passed on ontologically.

After our Zoom class (during COVID) I sent Susan a note asking her to help me understand better what she had said and to think with me about the difference between this sort of genetical inheritance and the ontological view of sin seen in the tract. Our conclusion was that it was correct to still say that original sin, the root problem, is relational. We also discerned that whereas the ontological view sees the sin presence in the being as permanent and unchanging, people can experience healing from inherited trauma. Genetically inherited trauma can be changed.